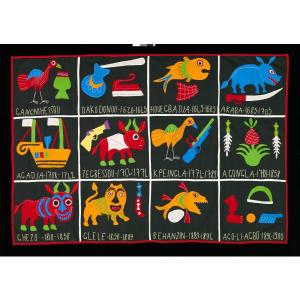

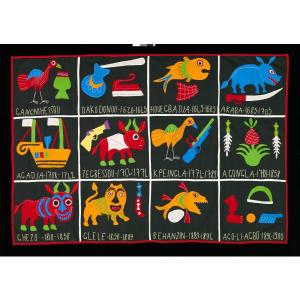

Point: "Wall Hanging" - Unknown (known to have come from the Fon Peoples in the late 20th Century

This cotton wall hanging comes from the Fon peoples of the Republic of Benin. Their culture is known for their colorful banners that contain a narrative of some sort. From a distance, one may not realize that all of these various images collectively form a storyline relative to the Fon peoples culture. Up close, one can see that a narrative of some sort is prevalent within the points, something that can be lost when viewing from afar.

Line: "Femme Sérèr" - Moustapha Dimé, 1992

In African art, proportions of areas on a piece relates to its importance in society. In this piece, we see a woman formed with the breasts and hip areas having a sharp contrast to the thinness of the body. The breasts and hips (made of mortar, pestle, and wood bowls) are prevalent to represent healthy births and nurturing. The piece gives us a glimpse into the expectations of women in African culture.

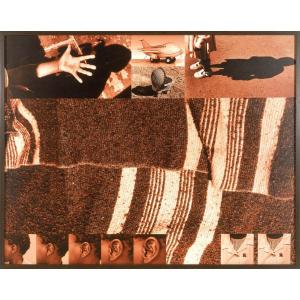

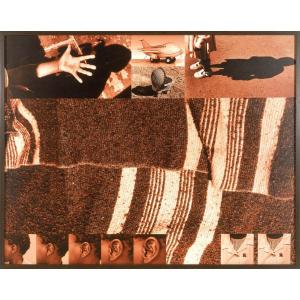

Form: "Open Letter to God" - Zwelethu Mthethwa, 2000

Mthethwa’s use of common colors and layering allows for this piece to appear to appear three dimensional, when it is really just two dimensional. The darker brown and more textured pieces seem to jump out, while lighter shades of brown depicting scenes rest in the background. Mthethwa’s goal in this piece was “to depict children as the silent, helpless witnesses to and victims of South Africa’s HIV/AIDS epidemic.” Although one may not be able to infer that at first glance, the piece becomes stronger when you see how images are linked to this idea (such as the child standing in the shade, the hand reaching out, etc.)

Movement: "Large study for 'Masquerader'" - Sokari Douglas Camp, 1981

This piece by Sokari Douglas Camp shows movement in two dimensional form. The emphasis on the darker shading of certain areas (the thick, hard lines situated near the upper arms and across the legs) demonstrate the rapid movements of the dancer. The dashes of color (most prevalent in the headdress) makes the viewer imagine the ferocity of the Masquerader’s movements. This piece was a personal favorite.

Color and Color Psychology: "Hongera Barack Obama" - Unknown, 2008

In “Hongera Barack Obama”, we are bombarded by the color orange. All of the orange shows unity within the piece. “Hongera Barack Obama” translates to “Congratulations Barack Obama”. The text on the piece, “Upendo Na Amani Ametujalia Mungu” translates to “God has blessed us with peace and love”. These two sentences relate to the color psychology of orange, which is the color of “the friendly warmth of the heart fire.”

Color and Color Psychology: "Portrait of a Woman" - Ibrahima Sall, 1967

“Portrait of a Woman” uses the contrast of its vibrant yellow and deeper blue background to draw in the viewer. Yellow represents optimism while blue represents spirituality and reserved elegance. Together, they portray a strong and hopeful future for the strong women of Africa. This piece immediately grabbed my attention and may have been my favorite at the museum.

Pattern: "Woman's Wrapper" - Unknown, known to come from the Yoruba peoples, mid 20th century

The complex pattern used on this cloth is known as “sun bebe”, or “lifting up the sun”. The pattern is created by keeping the indigo dye from reaching certain areas of the cloth through painting or stenciling. The name refers to beads brides-to-be wore when performing a private dance before their future husbands.

Texture: "Totem Pillar" - Lamidi Olonade Fakeye, 1972

This piece is completely hand carven and the intricacy is shown throughout. Fakeye developed very rigid textured areas, especially with the middle block, and the well-carved bodies. As with many pieces of African Art, the proportions are very important. The large breasts on the top figure represent fertility, while the large heads of the figures represent wisdom.

Balance: "Ka Cabala Voodoo" - Ouattara Watts, 1995

The balance of “Ka Cabala Voodoo” promotes a tranquil and religious feeling throughout. The two clay mounds at the top represent the mosques of West Africa and the the clay-esque surface represent various altars where one would make offerings. This piece is an example of approximate symmetry, as not all pieces are identical but they are similar.

Proportion: "Female figure with child" - Unknown, from Asante peoples, Late 19th to-mid 20th century

As mentioned earlier, proportion plays a large part in African Art. The proportion of a certain part in a figure shows its importance in culture and religion. In this piece, the large chair shows that the female had power in society (her long neck and tall figure also assert this). In a sense, it shows how she stands over others as a ruler. The large breasts represent fertility and the large head shows wisdom. The child breastfeeding shows a passing on of this wisdom and hope for a healthy future.

Rhythm: "Glance toward the Unknown" - Fathi Hassan, 1985

In “Glance toward the Unknown”, the rhythm of the scripture that forms the face brings intimacy and movement to the piece. We see the connection of man and written word, the scripture is seamlessly in rhythm with the human face. The writings are illegible though, showing that there is still an unknown distance between man and true religious connection. This was another personal favorite.

Emphasis: "Sheikh Amadou Bamba" - Gora Mbengue, Late 20th Century

The figure at the center of the painting is emphasized due to his vibrant white clothing. This man is Sheikh Amadou Bamba, who is a Sufi saint. The brightness of clothing compared to the rest of the painting emphasizes his figure more than any other. The neutral background allows the prominence of this holy figure to shine through.

Unity: "Brave New World II" - Theo Eshetu, 1999

When you look straight on at “Brave New World II”, you can see four mirrors reflecting the image of a movie out to the viewer. As one continues to stare at the image, the lines of the mirrors disappear and form one cohesive and unified image. When one looks from a side view, a whole new perspective is shown. We see the mirrors reflecting off one another and creating something similar to a combination of a kaleidoscope and a disco ball. It is quite a breathtaking and visually stunning piece. Along with “Portrait of a Woman” by Ibrahima Sall, this shared the position of being my favorite piece.